In November 2022, OpenAI’s release of ChatGPT triggered an earthquake in higher education. ChatGPT is perhaps the most famous example of Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI), or a larger umbrella category of computer models that ingest massive quantities of human-created data in order to learn patterns and generate new material that mimics that same content, whether images, video, music, or, in ChatGPT’s case, written text. A user can ask ChatGPT to write all sorts of things via a simple chat-based interface, from poems, recipes, and short stories, to (more problematically for teachers) entire essays, reading summaries, and answers to multiple-choice questions. Eighteen months later, we’re still trying to find our collective footing.

As a ThinqStudio faculty fellow and the Director of Digital Initiatives for CLAS, I’ve spent a lot of time over the past several semesters wrestling with these changes. I co-organized workshops to help instructors learn about Generative AI, from the basics of Large Language Models to convening a panel of faculty and their students who shared how they used these tools in their classes. I was part of a working group that drafted sample syllabus policies and other teaching resources around Generative AI for faculty to use in their classes. And I’ve taught students about some of these tools and topics in a course, Introduction to Digital Studies. So: what have I learned?

First, this is a new era for teaching. I’m typically a curmudgeon when it comes to the Silicon Valley hype machine. But we’ve reached an inflection point. Generative AI is not going anywhere; if anything, it will only get more ubiquitous, more powerful, and more deeply woven into our daily lives. As teachers, we can’t ignore this. In a way that is different from other tech developments, educators need to not only familiarize themselves with this new landscape, but to keep tabs on how it is changing. And it is changing quickly.

If you tried out ChatGPT after its release in November of 2022 - perhaps copying and pasting one of your essay prompts to see what it wrote in response - chances are good that you used the free version of ChatGPT based on the underlying model of GPT-3.5. And its response might have been mediocre to below-average: a tendency to hallucinate (ie. fabricate) citations and facts, an inability to retrieve information about current events, or a blandly generic writing style. But that’s changed. GPT-4 was released in March 2023 and powers the current subscription-based plan for ChatGPT (along with Microsoft’s Copilot tool). Many of the shortcomings you might have noticed in the free version of ChatGPT based on GPT-3.5 have been drastically reduced or even eliminated in GPT-4.

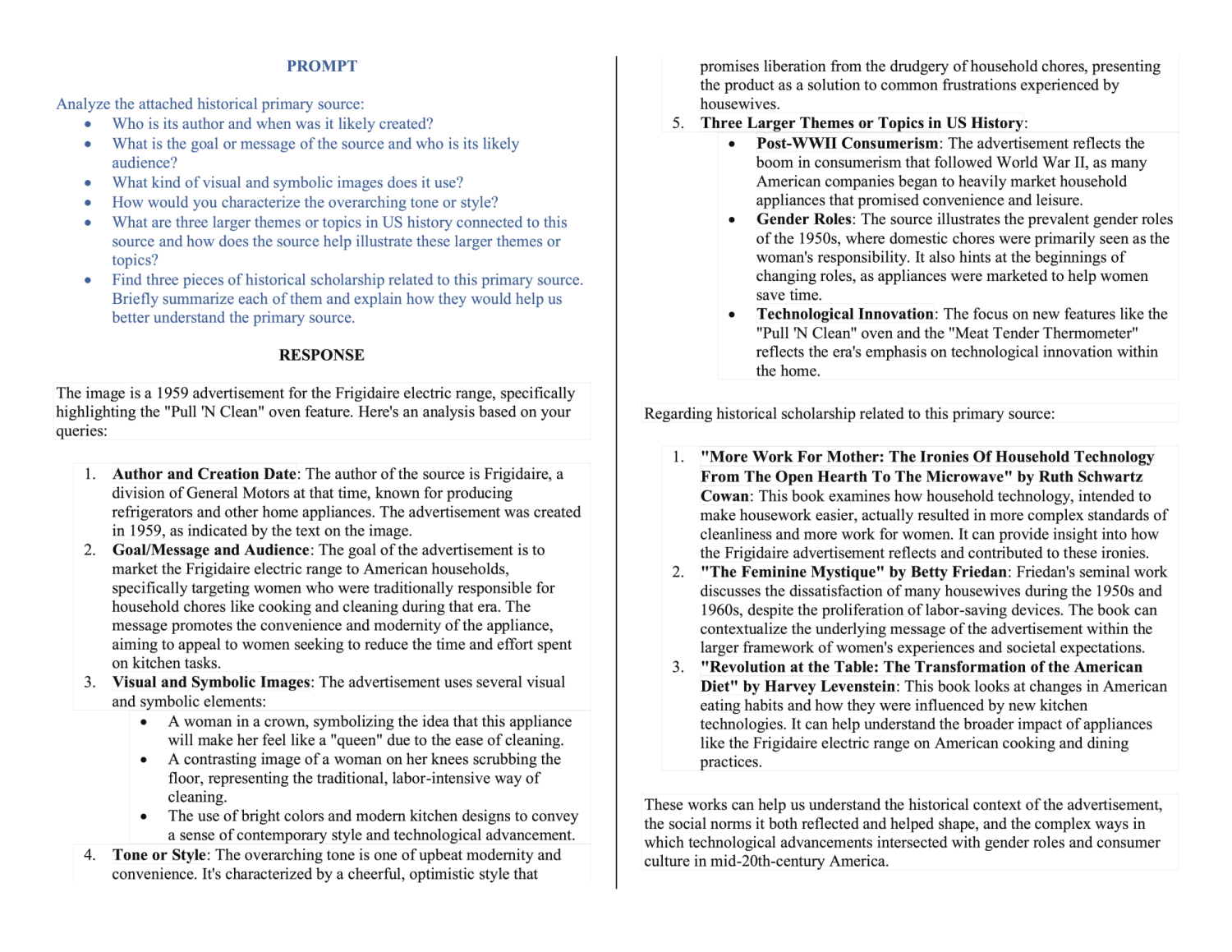

Take the following example. I teach HIST 1362: US History Since 1876, an introductory-level core humanities course for CLAS. During one class, I have students study America’s booming post-World War II consumer economy by looking at advertisements from the 1950s. The goal is to familiarize students with the topic while also teaching them how to closely read and interpret the imagery and symbols of consumer culture, such as this heavily gendered advertisement for a Frigidaire oven:

Frigidaire Advertisement (1959)

So what happens if I ask ChatGPT to analyze the above advertisement as if it were one of my students? When ChatGPT was first released in November of 2022, it wouldn’t have been able to do so. At the time, it could only handle text-based prompts that a user typed into the chat. Today? GPT-4 can handle not just typed prompts, but also entire PDF documents, photographs, or historical images like the above advertisement. And it can perform remarkably in-depth analysis. When given the Frigidaire advertisement, it correctly identified “the basics” of the source, unpacked some of its visual imagery, placed the source within a larger historical context, and even provided references and brief summaries of relevant articles and books related to the topic. Here are the instructions I gave to ChatGPT along with its full response; I hope it drives home just how rapidly this technology has advanced:

Prompt and Response from ChatGPT (GPT-4) generated on March 3, 2024

Instructors don’t need to become experts on Generative AI. But they do need to develop more familiarity with some of the main applications in this field and any major new developments. I’ve found the work of Ethan Mollick, a business school professor who writes about AI in higher education, to be a good starting point. He and Lilach Mollick have produced a short video series, Practical AI for Instructors and Students, that offers an accessible introduction geared towards educators. Ethan Mollick’s Substack newsletter One Useful Thing, meanwhile, is a useful way to keep up with new developments. But far and away the most effective way to get up to speed is to actually use these tools. If you don’t want to pay $20 a month for the paid version of ChatGPT, then you can access the underlying GPT-4 model through Microsoft’s Copilot tool. Set aside several hours to simply experiment with the tools and you’ll get a better sense for their capabilities and limitations than you would from reading dozens of articles about them.

This brings me to my second lesson learned: we need to actively adapt our teaching to this new landscape. For awhile, I told colleagues that it was not the responsibility of any one instructor to revamp their entire curriculum overnight, instead reassuring them that they could wait for the dust to settle around Generative AI and see where we ended up. Well, the dust has settled. We need to start making changes to our teaching.

At a minimum, everyone needs to decide what kind of policies you want for specific courses regarding the allowable use of Generative AI. Students need clarity. I would start with the pros and cons table of these three sample syllabus policies. Choose the policy that most closely aligns with your individual course and then tailor and tweak it accordingly. Once again, it’s imperative to become at least passably familiar with what the current tools can and cannot do. Think through the major assignments and goals of a course. Does it make sense to allow students to use ChatGPT for, say, brainstorming ideas for a project? Drafting an outline of a paper? Locating potential sources? Then think about enforcement. What happens if you receive an essay that you suspect was written by ChatGPT? How are you going to talk to the student?

The issue of enforcement is a bugbear for many instructors, who continue to focus on Generative AI’s implications academic integrity, plagiarism, and cheating. And it’s true that students have and will continue to use these tools to submit work that they did not produce themselves. There are no silver bullets coming from educational institutions. Nor should we expect the giant, profit-driven companies building these tools to come up with solutions. So-called “AI detection” software is, at best, fool’s gold — unreliable, easy to bypass, and prone to false positives for non-English speakers. Let me repeat: there is no software that can reliably “prove” that a piece of text was written by ChatGPT.

Rather than focusing so much on academic integrity, I would encourage educators to instead think more constructively about how you can integrate Generative AI into your teaching in ways that actually help students learn. One strategy is to use Large Language Models as tutors or coaches. During one of our workshops this past fall, Professor Dawn Gregg shared how she had started using ChatGPT in her online course ISMG 6020: Python Programming Fundamentals. In that class, she had her students use ChatGPT as a tutor to help document and debug their Python code, provide examples of programming concepts, and generate practice questions. Professor Gregg reported some remarkable results. Compared to the previous semester she taught the class, student attrition rate went down and the quality of their work went up. Moreover, Professor Gregg reported a dramatic decrease in the number of student emails she received, as ChatGPT helped them get unstuck on a problem before immediately asking the professor for help.

This example can apply to other disciplines. Large Language Models like ChatGPT have the potential to serve as a pseudo-teaching assistant or brainstorming partner. Precisely because the underlying model is built by establishing connections between different words, phrases, and concepts across massive quantities of text, they are often capable of arriving at surprisingly creative ideas. They can help students get unstuck, work through tricky concepts, or provide basic feedback. Rather than replacing an instructor, these tools can take on some of the drudgery of teaching, such as writing “passive voice” yet again in the margins of a student essay. Ideally, using Large Language Models in this way can free up our time to focus on higher-order concepts and thinking skills.

The third lesson I’ve learned is that we need to answer an overriding question from students: why am I doing this? By “this,” I’m referring to assignments, activities, skills, and approaches that educators have long taken for granted. We need to take the question of “why am I doing this?” more seriously and address it more directly. We need to drive home to students that it’s not about getting a grade for a finished product, but about honing the skills that go into creating that product. We then need to explain precisely and concretely what those skills are and why they are relevant and worthwhile. We can’t just gesture to things like “critical thinking,” “communication,” or “research” without making them relatable and applicable to students’ lives.

Or, we can use this as a chance to rethink some of our assignments entirely. Take a classic assignment in my own discipline of history: the essay. In HIST 1362: US History Since 1876, I might give students the following essay prompt: “Did the 1968 Democratic National Convention have a largely positive or a largely negative impact on modern American political history? Write a five-page essay that makes your claim, supported with both primary and secondary sources.” For years, the output for that assignment - the written essay - was a decent way to evaluate students on skills at the heart of historical inquiry: research, synthesis, critical thinking, and, of course, written communication and rhetoric. Today, GPT-4 can write that same essay better than 80-90% of my students. It can provide context, locate relevant scholarship, synthesize material into a clear argument, and use impeccable writing mechanics to make its claim.

Given this reality, I think it is completely reasonable for an overworked and overstretched student in my class to ask: why am I doing this? Why should I spend hours and hours on an assignment that a chatbot can do better than me and in a fraction of the time? After all, the vast majority of my students will never have to sit down and write a five-page essay as part of their job - something that will be even more true as Generative AI tools get further integrated into writing platforms.

Accordingly, I’ve started moving away from essays and towards other kinds of experiential assignments in the class. Instead of an essay prompt about the 1968 Democratic National Convention, I now have students engage in a multi-day roleplaying simulation in which they each take on the role of a delegate, protestor, or journalist attending the convention. The assignment helps them understand the historical significance of the convention, but in a way that is far more engaging, memorable, and effective than having them slog their way through yet another five-page essay.

If Generative AI has shaken up long-standing teaching practices in higher education, then ThinqStudio is exactly the kind of community to help us adapt to these changes. Teaching in an era of Generative AI will require experimentation, creativity, and a willingness to challenge the status quo - in other words, the guiding principles of ThinqStudio itself. From “playful pedagogy” to ungrading, ThinqStudio has long been helping instructors rethink some of the core tenets of higher education. Perhaps most importantly, ThinqStudio provides a community of people to think through these changes collectively. After all, none of us should have to navigate this unfamiliar landscape alone.